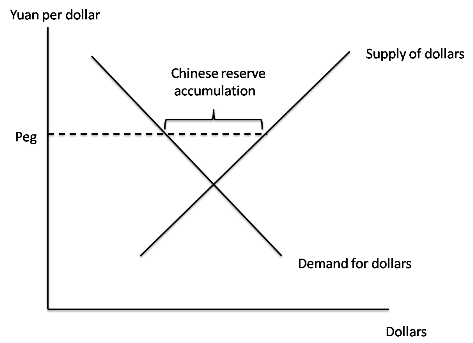

Yet another great post by Paul Krugman on the significance of rising debt levels. First here’s the image that went with the post:

And now the post itself:

Earlier this week I gave a talk about the state of the crisis at Princeton’s Plasma Physics Lab, and one audience member asked a really good question: if the problem is that interest rates are at the zero lower bound, why should we worry about government borrowing? After all, doesn’t that mean that the government can borrow at a zero rate?

Now, part of the answer is that you really don’t want governments financing themselves largely with very short-term debt — that makes them too vulnerable to liquidity crises. But even long-term rates are low — the real interest rate on 10-year bonds is below 1.5 percent.

And if you do the arithmetic of debt service, that really does seem to suggest that debt isn’t a problem. To stabilize the real value of debt, all the government has to do is pay the real interest on it. So suppose that we add debt equal to 100 percent of GDP, which is much more than currently projected; servicing that debt should cost only 1.4 percent of GDP, or 7 percent of federal spending. Why should that be intolerable?

And even that, you could argue, is too pessimistic. To stabilize the debt/GDP ratio, all you need is to pay r-g, where r is the real interest rate and g the economy’s real growth rate; and right now r-g looks, ahem, negative.

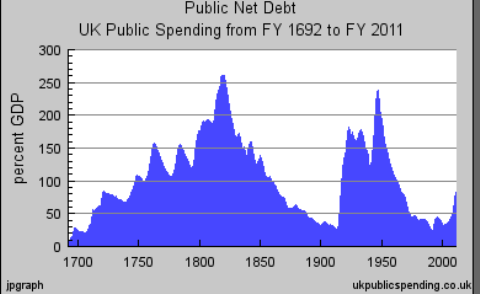

And this benign view of debt isn’t just hypothetical: countries have, in reality, run up immense debt/GDP ratios without going insolvent: see the history of Britain, above.

So what’s the problem? Confidence. If bond investors start to lose confidence in a country’s eventual willingness to run even the small primary surpluses needed to service a large debt, they’ll demand higher rates, which requires much larger primary surpluses, and you can go into a death spiral.

So what determines confidence? The actual level of debt has some influence — but it’s not as if there’s a red line, where you cross 90 or 100 percent of GDP and kablooie; see the chart above. Instead, it has a lot to do with the perceived responsibility of the political elite.

What this means is that if you’re worried about the US fiscal position, you should not be focused on this year’s deficit, let alone the 0.07% of GDP in unemployment benefits Bunning tried to stop. You should, instead, worry about when investors will lose confidence in a country where one party insists both that raising taxes is anathema and that trying to rein in Medicare spending means creating death panels.

This is important. In particular given what is being said by the likes of George Osborne:

No one doubts that there were massive failures of financial regulation over the last decade.

No one seriously defends the fiscal rules, once spelt out in a Mais Lecture like this, which proved unable to prevent the Government running a budget deficit at the peak of the boom.

But we will not draw all the right lessons for the future unless we understand the deep macroeconomic roots of the crisis.

Much has already been written about what went wrong. Much more is yet to be written.

Perhaps the most significant contribution to our understanding of the origins of the crisis has been made by Professor Ken Rogoff, former Chief Economist at the IMF, and his co-author Carmen Reinhart.

In a series of papers and now a book, they have demonstrated in exhaustive historical and statistical detail that while it always seems in the heat of the crisis that ‘this time is different’, the truth is that it almost never is.

As Rogoff and Reinhart demonstrate convincingly, all financial crises ultimately have their origins in one thing – rapid and unsustainable increases in debt.

As they write, “if there is one common theme… it is that excessive debt accumulation, whether it be by the government, banks, corporations, or consumers, often poses greater systemic risks that it seems during a boom.”

So while the specific financial innovations and failures of regulation that contributed to the credit crunch were new, the underlying macroeconomic warning signs were depressingly familiar from many dozens of crises in the past.

In this context, all the signals were flashing red for the UK economy: a rapid increase in household and bank balance sheets, soaring asset prices, a persistent current account deficit, and a structural budget deficit even at the peak of the boom.

Our banks became more leveraged than American banks, and our households became more indebted than any other major economy in history.

And in the aftermath of the crisis our public debt has risen more rapidly than any other major economy.

So while private sector debt was the cause of this crisis, public sector debt is likely to be the cause of the next one.

As Ken Rogoff himself puts it, “there’s no question that the most significant vulnerability as we emerge from recession is the soaring government debt. It’s very likely that will trigger the next crisis as governments have been stretched so wide.”

The latest research suggests that once debt reaches more than about 90% of GDP the risks of a large negative impact on long term growth become highly significant.

As is clear, Krugman is refering to the now bandied around figure that once debt goes over 90% trouble arises. But as is even clearer from the graph above, this simply doesn’t apply when there is confidence that this debt will get paid off. So where does this figure come from. Essentially it has arisen from the very impressive work of Reinhart and Rogoff. I read Reinhart and Rogoff’s book and that 90% figure didn’t jump out that strongly, nor did the book seem to give strong support for the Conservative/Fianna Fail commitment to cuts regardless of consequence. So I was a bit surprised when I say Ken Rogoff name onthat letter to the Sunday Times, which ostensibly supported Osborne’s proposals.

I think I was right to be surprised given that Reinhart and Rogoff wrote an article for the FT at the end of January arguing that:

Given these risks of higher government debt, how quickly should governments exit from fiscal stimulus? This is not an easy task, especially given weak employment, which is again quite characteristic of the post-second world war financial crises suffered by the Nordic countries, Japan, Spain and many emerging markets. Given the likelihood of continued weak consumption growth in the US and Europe, rapid withdrawal of stimulus could easily tilt the economy back into recession.

And given that Reinhart and Rogoff’s work is being used by the likes of Martin Wolf to argue in favour of continued stimulous. Wolf points out that Reinhart and Rogoff have shown that you the debt almost alwaysincreases during a recession:

In their work on the history of financial crises, Carmen Reinhart of the University of Maryland and Kenneth Rogoff of Harvard University note that “the real stock of debt nearly doubles†in crisis-hit countries.*

Perhap’s as leftfootforward argues the letter to the Sunday Times actually was not in support of Osborne. The letter does state that

The exact timing of measures should be sensitive to developments in the economy, particularly the fragility of the recovery.

Regardless, not to disparage Ken Rogoff, but as Osborne is clearly arguing from autority here. ‘If the former chief economist of the IMF says it is must be true.’ He should perhaps listen to a former chief economist of the World Bank who recently gave his opinion of Osborne’s policies:

On the suggestion, put about by George Osborne, among others, that Britain is at risk of default: “I say you’re crazy — economically you clearly have the capacity to pay. The debt situation has been worse in other countries at other times. This is all scaremongering, perhaps linked to politics, perhaps rigged to an economic agenda, but it’s out of touch with reality. One of the advantages that you have is that you have your own central bank that can buy some of these bonds to stabilise their price.”