via Economist’s View Again, this is the biggest things since the Great Depression. It still matters.

This comes from the Minneapolis Fed. More graphy goodness at the source.

via Economist’s View Again, this is the biggest things since the Great Depression. It still matters.

This comes from the Minneapolis Fed. More graphy goodness at the source.

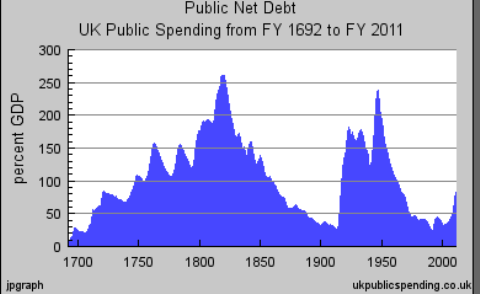

Yet another great post by Paul Krugman on the significance of rising debt levels. First here’s the image that went with the post:

And now the post itself:

Earlier this week I gave a talk about the state of the crisis at Princeton’s Plasma Physics Lab, and one audience member asked a really good question: if the problem is that interest rates are at the zero lower bound, why should we worry about government borrowing? After all, doesn’t that mean that the government can borrow at a zero rate?

Now, part of the answer is that you really don’t want governments financing themselves largely with very short-term debt — that makes them too vulnerable to liquidity crises. But even long-term rates are low — the real interest rate on 10-year bonds is below 1.5 percent.

And if you do the arithmetic of debt service, that really does seem to suggest that debt isn’t a problem. To stabilize the real value of debt, all the government has to do is pay the real interest on it. So suppose that we add debt equal to 100 percent of GDP, which is much more than currently projected; servicing that debt should cost only 1.4 percent of GDP, or 7 percent of federal spending. Why should that be intolerable?

And even that, you could argue, is too pessimistic. To stabilize the debt/GDP ratio, all you need is to pay r-g, where r is the real interest rate and g the economy’s real growth rate; and right now r-g looks, ahem, negative.

And this benign view of debt isn’t just hypothetical: countries have, in reality, run up immense debt/GDP ratios without going insolvent: see the history of Britain, above.

So what’s the problem? Confidence. If bond investors start to lose confidence in a country’s eventual willingness to run even the small primary surpluses needed to service a large debt, they’ll demand higher rates, which requires much larger primary surpluses, and you can go into a death spiral.

So what determines confidence? The actual level of debt has some influence — but it’s not as if there’s a red line, where you cross 90 or 100 percent of GDP and kablooie; see the chart above. Instead, it has a lot to do with the perceived responsibility of the political elite.

What this means is that if you’re worried about the US fiscal position, you should not be focused on this year’s deficit, let alone the 0.07% of GDP in unemployment benefits Bunning tried to stop. You should, instead, worry about when investors will lose confidence in a country where one party insists both that raising taxes is anathema and that trying to rein in Medicare spending means creating death panels.

This is important. In particular given what is being said by the likes of George Osborne:

No one doubts that there were massive failures of financial regulation over the last decade.

No one seriously defends the fiscal rules, once spelt out in a Mais Lecture like this, which proved unable to prevent the Government running a budget deficit at the peak of the boom.

But we will not draw all the right lessons for the future unless we understand the deep macroeconomic roots of the crisis.

Much has already been written about what went wrong. Much more is yet to be written.

Perhaps the most significant contribution to our understanding of the origins of the crisis has been made by Professor Ken Rogoff, former Chief Economist at the IMF, and his co-author Carmen Reinhart.

In a series of papers and now a book, they have demonstrated in exhaustive historical and statistical detail that while it always seems in the heat of the crisis that ‘this time is different’, the truth is that it almost never is.

As Rogoff and Reinhart demonstrate convincingly, all financial crises ultimately have their origins in one thing – rapid and unsustainable increases in debt.

As they write, “if there is one common theme… it is that excessive debt accumulation, whether it be by the government, banks, corporations, or consumers, often poses greater systemic risks that it seems during a boom.”

So while the specific financial innovations and failures of regulation that contributed to the credit crunch were new, the underlying macroeconomic warning signs were depressingly familiar from many dozens of crises in the past.

In this context, all the signals were flashing red for the UK economy: a rapid increase in household and bank balance sheets, soaring asset prices, a persistent current account deficit, and a structural budget deficit even at the peak of the boom.

Our banks became more leveraged than American banks, and our households became more indebted than any other major economy in history.

And in the aftermath of the crisis our public debt has risen more rapidly than any other major economy.

So while private sector debt was the cause of this crisis, public sector debt is likely to be the cause of the next one.

As Ken Rogoff himself puts it, “there’s no question that the most significant vulnerability as we emerge from recession is the soaring government debt. It’s very likely that will trigger the next crisis as governments have been stretched so wide.”

The latest research suggests that once debt reaches more than about 90% of GDP the risks of a large negative impact on long term growth become highly significant.

As is clear, Krugman is refering to the now bandied around figure that once debt goes over 90% trouble arises. But as is even clearer from the graph above, this simply doesn’t apply when there is confidence that this debt will get paid off. So where does this figure come from. Essentially it has arisen from the very impressive work of Reinhart and Rogoff. I read Reinhart and Rogoff’s book and that 90% figure didn’t jump out that strongly, nor did the book seem to give strong support for the Conservative/Fianna Fail commitment to cuts regardless of consequence. So I was a bit surprised when I say Ken Rogoff name onthat letter to the Sunday Times, which ostensibly supported Osborne’s proposals.

I think I was right to be surprised given that Reinhart and Rogoff wrote an article for the FT at the end of January arguing that:

Given these risks of higher government debt, how quickly should governments exit from fiscal stimulus? This is not an easy task, especially given weak employment, which is again quite characteristic of the post-second world war financial crises suffered by the Nordic countries, Japan, Spain and many emerging markets. Given the likelihood of continued weak consumption growth in the US and Europe, rapid withdrawal of stimulus could easily tilt the economy back into recession.

And given that Reinhart and Rogoff’s work is being used by the likes of Martin Wolf to argue in favour of continued stimulous. Wolf points out that Reinhart and Rogoff have shown that you the debt almost alwaysincreases during a recession:

In their work on the history of financial crises, Carmen Reinhart of the University of Maryland and Kenneth Rogoff of Harvard University note that “the real stock of debt nearly doubles†in crisis-hit countries.*

Perhap’s as leftfootforward argues the letter to the Sunday Times actually was not in support of Osborne. The letter does state that

The exact timing of measures should be sensitive to developments in the economy, particularly the fragility of the recovery.

Regardless, not to disparage Ken Rogoff, but as Osborne is clearly arguing from autority here. ‘If the former chief economist of the IMF says it is must be true.’ He should perhaps listen to a former chief economist of the World Bank who recently gave his opinion of Osborne’s policies:

On the suggestion, put about by George Osborne, among others, that Britain is at risk of default: “I say you’re crazy — economically you clearly have the capacity to pay. The debt situation has been worse in other countries at other times. This is all scaremongering, perhaps linked to politics, perhaps rigged to an economic agenda, but it’s out of touch with reality. One of the advantages that you have is that you have your own central bank that can buy some of these bonds to stabilise their price.”

Irish Times reports:

THE NUMBER of vacant houses or apartments in the State stands at 345,000, or 17 per cent of all housing, according to new report published today by the Urban Environment Project at University College Dublin.

Came across this via The Cedar Lounge, this situation with Greece is getting more and more ridiculous. Now, some German government politicians are calling on Greece to sell off some of it’s Islands to finance its debt.

Greece should consider selling some of its uninhabited islands to cut its debt, according to political allies of German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Full story on the beeb.

About 30-40 mins after reading Andrew’s thought provoking piece on the Better Questions series in Seomra Sproi, I was watching Tuesday’sDaily Show. In it they make an amuzing point that the recent credit card reform act in the US does little more than make credit card companies and the state than enforces it little more ethical than the mob. As the former mob loan shark says “We might have broken your legs, maybe pushed back your nuckles. You might have fallen down the stairs, accidentally. But if you didn’t pay, we never took your house. We never took your house.” Anyway, it made me think of how so much of the left in recent years will talk about everything apart from ‘the economy’. Andrew’s post drew me back to a post by Chris Dillow over at Stumbling and Mumbling where he says “I blame the 80’s”. In Chris’s post he gives an anecdote about the Andrw Glyn, the late Oxford economist. Dr. Glyn, who despite dieing 2-3 months before I discovered his writings, is something of an inspiration to me. Or perhaps it would be better to say an aspiration.

Anyway here’s the anecdote

I remembered an exchange at Oxford in the 80s between Andrew Glyn and a whiney London woman. Andrew had just given a talk outlining a Marxist view of Thatcherism. Whiney woman: “Yah, Andrew. I agree with your analysis, but don’t you think we have to build a radical feminist critique?” Andrew: “No.”

In America over the weekend it came out that

The prices of US goods and services, excluding food and fuel, fell last month for the first time since 1982…The closely watched “core†consumer price index fell 0.1 per cent in January, labour department figures showed on Friday, as prices for new cars and housing dropped from the previous month.

While this is hardly shocking. It does bang home the point that we are not experiencing inflationary pressures and that spending has not picked up sufficiently for government spending to be cut back.

First, Part 3 from Ian Dury

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CIMNXogXnvE]

Second, Part 4 from Maxim Pinkovskiy, Xavier Sala-i-Martin

We use a parametric method to estimate the income distribution for 191 countries between 1970 and 2006. We estimate the World Distribution of Income and estimate poverty rates, poverty counts and various measures of income inequality and welfare. Using the official $1/day line, we estimate that world poverty rates have fallen by 80% from 0.268 in 1970 to 0.054 in 2006. The corresponding total number of poor has fallen from 403 million in 1970 to 152 million in 2006. Our estimates of the global poverty count in 2006 are much smaller than found by other researchers. We also find similar reductions in poverty if we use other poverty lines. We find that various measures of global inequality have declined substantially and measures of global welfare increased by somewhere between 128% and 145%. We analyze poverty in various regions. Finally, we show that our results are robust to a battery of sensitivity tests involving functional forms, data sources for the largest countries, methods of interpolating and extrapolating missing data, and dealing with survey misreporting.

[Empahasis mine]

For those of you who have been trying to follow the Obama heathcare reform here’s a helpful flow chart. (A bigger version is here) First thing’s first. Obama is NOT introducing an NHS. He is not introducing a nationalised healthcare system. What he is doing is regulating existing private insurers, introducing insurance subsidies for people on low income and creating a ‘public option’ i.e. a publicly owned insurer.

From the Irish Economy blog:

It is worth taking a closer look at the Quarterly National Household Survey results from last week. The difference between the public and private sectors has attracted some comment but there is much more going on here. In particular, the major trend that stands out is the disastrous collapse in working class employment with growing differences between the position of those with third level education and those without. The need for serious commitments in enterprise and employment policy, education and training policy, and housing/ mortgage support is clear.

I meant to post a link to this back at the end of February when it went up. But I didn’t. Regardless, this article by Barry Eichengreen lays out Ireland’s problem clearer than anything else I’ve seen. Emerald Isle to Golden State